|

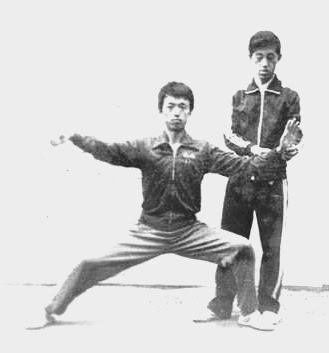

| Chenjiagou mural - Chen Xin passing on the principles and rules of Chen Taijiquan |

Wang Zongyue’s classic manual of Taijiquan advises that “an

initial error of one inch can result in a deviation of a thousand miles.

Practitioners must study and understand the principles very carefully.” Taijiquan

is a complex discipline and to have any hope of reaching a competent level great

care and attention must be given to your Taijiquan study from the start. It’s

easy, especially for beginners, to ignore what seem to be inconsequential

details. But making this mistake can cause a learner to misunderstand the art,

ultimately preventing them from reaching a true understanding of Taijiquan.

On the training floor many students fail to really pay

conscious attention to their practice, paying little more than lip service to following

Taiji principles. Filled with their own ideas about what Taijiquan is they don’t

listen carefully to the instructions given by their teachers. In many cases they

may practice hard but their physical effort is not matched by any deep thought

or reflection. The end result, they find it impossible to distinguish between Taijiquan

principles and other ideas or disciplines. Their reward after spending in some

cases decades of training is a failure to obtain any true Taijiquan skill.

Following from that depressing statement the obvious question

- what is meant by true Taijiquan skill? Answering this fully is way beyond the

scope of a single blog post, but as a starting point we could consider the two

vital and overarching qualities of peng and ding (as in zhongding). Peng or “ward off” is first of Taijiquan’s

four basic types of trained force or “jin”. It is characterised by a soft,

expansive power that is usually expressed in an upward and forward direction.

Peng is not applied simply by pushing hard into an opponent, but is applied

according to their situation. Zhongding simply stated refers to “central

equilibrium” or, in practical terms, the ability to maintain balance and stability

even where an outside force is being applied against any part of your body.

This type of stability is realised when a practitioner can move easily and

instinctively in any direction in accord with the direction and strength of any

attack. Key to maintaining this state is the ability to maintain focus upon the

dantian automatically readjusting it to keep balance. Finding and developing a

connection to the dantian in the first place requires considerable mindful practice

as the body shape is moulded into the correct shape while simultaneously the

correct energetic state is slowly cultivated.

To achieve these two qualities the various parts of the body

must be carefully integrated and in Taijiquan parlance “all excesses and

deficiencies must be eliminated.” Again, in practical terms, this means that

each time an error is pointed out by a teacher or recognised by a student it

should be worked upon and corrected immediately. The type of integration we are

talking about is no less that the total participation and cooperation of every

part of the body.

Taijiquan theory provides many pointers to help us work towards

this whole body harmonisation. One example: the rule that “jin or power comes

from the feet, is changed or transformed through the legs, directed by the

waist and expressed by the hands.” How can a practitioner hope to develop the necessary

sensitivity to this distinct kind of sequential transference of power through

their body without approaching their training with the greatest care and

attention. The careless practitioner puts all of his attention on the end point

of an action whether it be a punch, throw, lock etc. The practitioner who has

understood the method pays attention to where their jin comes from, how to store

it, control it and only then how to use it in the most efficient way. This

concept has been explained through an analogy where the body is compared to an

army going into battle. Here the lower body is represented by the rear of the

army that provides the food and ammunition to be used by the front line troops –

the upper body. Without sufficient supplies the troops will soon be defeated.

Similarly, without a strong source a practitioner’s techniques are unlikely to succeed.