|

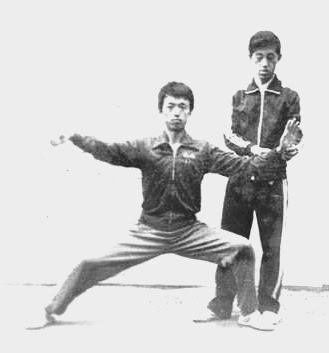

| Searching for the fine details of posture- a young instructor in the Chenjiagou Taijiquan School correcting Zhan Zhuang |

At the same time, like any other martial art, Taijiquan requires

them to set their sights high if they are to develop real and effective skills.

Simply, they must approach training with ambition. The first time I trained in

China back in 1997 I bought a bootleg disc of Wang Xian and his disciples

demonstrating the breadth of the Chen Taijiquan system. To say I loved the disc

would be an understatement! At the time my eyes were untrained to many of the

subtleties of Taijiquan, but it had everything - power, speed, coordination and

a tight focus and togetherness when

groups of instructors demonstrated. The last performance was Wang Xian himself explosively

demonstrating the Xinjia Yilu on the banks of the Yellow River. When he reached

the end of the form and quietly closed, the following simple message played across

the screen- “If you want to be better than everyone else, train harder than

everyone else” - pretty ambitious right?!

Going back a further generation Chen Zhaopi, the teacher most

credited with sparking the modern resurgence of Taijiquan in Chenjiagou,

described an individual’s progressive advancement from beginner to advanced

practitioner via three stages: in the first, a learner must open their joints

training the overtly physical aspects of the art; the second stage encompassed

the long journey of understanding Taijiquan’s neijin or internal energy; the

third he described as “continuous movements executed in one breath.” This

elevated level represented the height of perfection: with a complete integration

of form and spirit; body completely balanced and unrestrained; and movements

natural and instinctive. Reaching this level is referred to as shen ming, or "divine

realisation".

|

| A youthful Chen Zhenglei teaching the next generation |

Getting down

to day-to-day training we’re told to relax and not to “try” too hard; to be

natural and don’t force it; to cast aside stiff energy etc. All the while

continually having our frame adjusted to a place where the legs are literally

trembling with the effort. I remember a training session with Chen Xiaowang

where someone asked about the pain they were experiencing in their legs and if

it ever got easier. His oblique answer was simply to say, “don’t put so much

importance on the pain in your legs.” In other words, just because the legs are

hurting no need to add to that by fixating on it. If you’re doing Taijiquan

properly your legs are going to work hard. Taijiquan has a saying “concentrate on one thing lose everything.” No matter how hard you train if you

pay too much attention to any one thing you will move away from the ultimate

aim that is no less than the total integration of internal and external,

physicality and consciousness.

Taijiquan itself makes no apologies for its paradoxical nature. The

very name of the system is drawn from the philosophical concept of Taiji – it

is the martial art of balance and change. It is up to each individual to

reconcile the apparent contradictions for themselves. This area probably

confounds western Taijiquan students the most. For example many athletically

able students are overly concerned with external appearance and shape – whether

it be in terms of strength, flexibility etc. It’s there that they get their

positive strokes from others who also don’t see the whole picture. And to be

very clear this is not to diminish the fundamental importance of strength,

flexibility etc. This type of student can find it very hard to open up their

mind. During a training session with one of the younger generation teachers from Chenjiagou, a

strong and flexible individual stretched out into a wide and low posture. The

teacher’s correction was to lift the posture up and advise him to put

attention to loosening his kua and

rounding his dang (crotch). Although

the position was low, it was locked in such a way that the dang strength that is a vital part of Chen Taijiquan was totally

lacking. The immediate response – “What exercise can I do to loosen it?” -

completely missing the point that this was not something that was going to be

corrected by grinding out some reps.

|

| Another face of Taijiquan - Chen Zhaokui traing qinna |

Taijiquan

is built around the qualities of agility and changeability. It requires us to

aim high but at the same time do today’s work.

Chinese culture is imbued by the Daoist tradition and an acceptance of

seemingly contradictory aspects if we are to see a thing in its entirety. The

following passage from the Inner Chapters of Zhuangzi point simultaneously to

the need for careful instruction, effort and time while being mentally calm,

free and ungrasping.”

“Neither

deviate from your instructions, nor hurry to finish. Do not force things. It is

dangerous to deviate from instruction or push for completion. It takes a long time to do a thing properly. Once

you do something wrong it may be too late. Can you afford to be careless? Follow

with whatever happens and let your mind be free; stay centred by accepting

whatever you are doing. This is the ultimate… It is best to leave everything to

work naturally…”